The Mathematics of Avalanche Trajectories

In the realm of disaster geometry, few phenomena showcase the interplay of mathematical principles and natural forces as dramatically as avalanches. This article delves into the geometric underpinnings that govern avalanche paths, exploring how slope angles, terrain features, and other factors contribute to avalanche prediction and mitigation strategies.

Slope Angles: The Critical Factor

The angle of a slope is perhaps the most crucial geometric factor in avalanche formation and propagation. Research has shown that most avalanches occur on slopes between 30° and 45°. This range represents a critical balance where snow accumulation is possible, yet gravitational forces are sufficient to overcome friction and trigger movement.

Key Angle Thresholds:

- < 25°: Generally stable, low avalanche risk

- 30° - 45°: Prime avalanche terrain

- > 50°: Snow typically sloughs off before accumulating

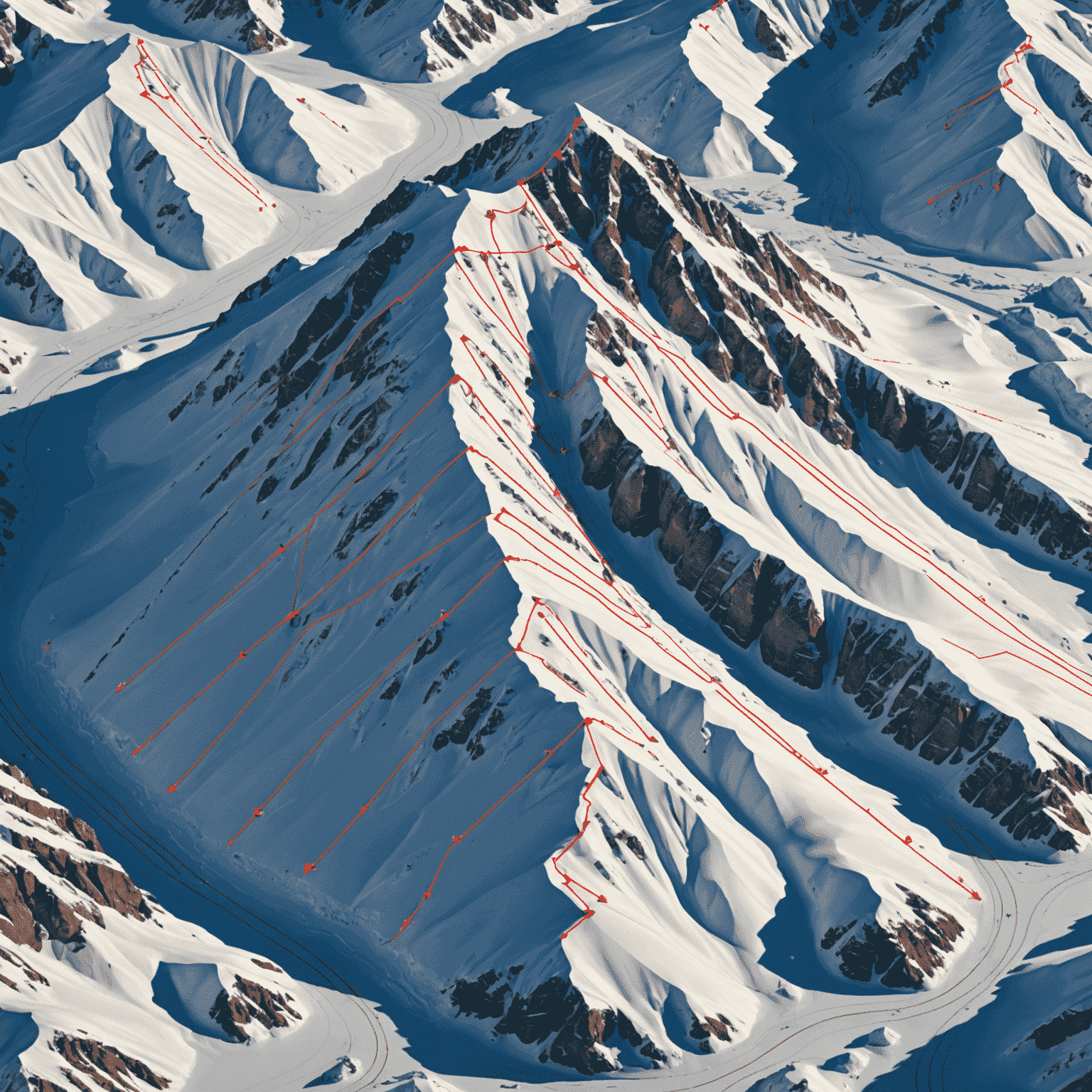

Terrain Features and Geometric Patterns

Beyond slope angle, the geometric configuration of terrain features plays a significant role in avalanche dynamics. Convex slopes, for instance, create tension in the snowpack, increasing the likelihood of fractures. Concave slopes, on the other hand, can act as natural catchment areas, potentially increasing the volume and destructive power of an avalanche.

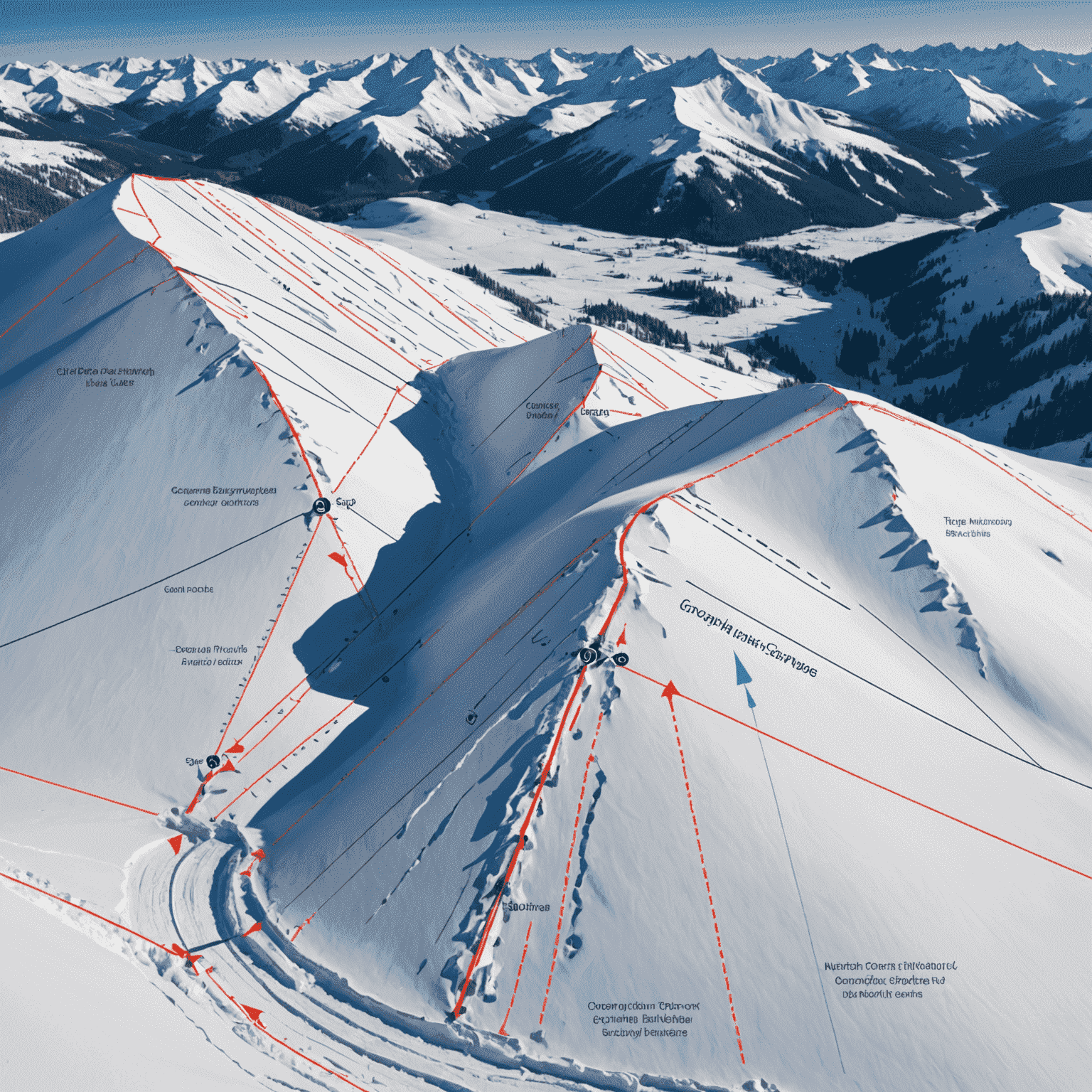

Mathematical Models for Prediction

Advanced mathematical models incorporate these geometric principles to predict avalanche trajectories. These models often use differential equations to describe the motion of snow masses, taking into account factors such as:

- Initial acceleration due to gravity

- Frictional forces along the path

- Air resistance and entrainment

- Terrain irregularities and obstacles

One common model is the Voellmy-Salm model, which uses a combination of Coulomb friction and turbulent friction to describe avalanche flow. This model can be expressed as:

Sf = μ cos θ + (g/ξ) u2

Where Sf is the total friction, μ is the Coulomb friction coefficient, θ is the slope angle, g is gravity, ξ is the turbulent friction coefficient, and u is the flow velocity.

Geometric Approaches to Mitigation

Understanding the geometry of avalanches allows for more effective mitigation strategies. These can include:

- Deflection Structures: Wedge-shaped barriers designed to divert avalanche flow.

- Catchment Basins: Engineered depressions to capture and slow avalanche debris.

- Terracing: Altering slope geometry to reduce continuous acceleration paths.

Conclusion: The Power of Geometric Analysis

The study of avalanche trajectories through the lens of geometry provides crucial insights for disaster prevention and management. By understanding the mathematical relationships between terrain features, snow physics, and gravitational forces, we can better predict, model, and mitigate the risks associated with these powerful natural phenomena.

As our computational capabilities advance, so too does our ability to create more sophisticated geometric models of avalanche behavior. This ongoing research not only enhances our understanding of disaster geometry but also contributes to the development of more effective risk assessment tools and protective measures for mountain communities worldwide.